The IRS offers a “grace period” for your first Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) at age 70, allowing you to delay it until April 1 of the following year.

While this seems helpful, it’s a financial trap. Delaying means taking two RMDs in a single tax year, creating an artificial income spike.

This can push you into a higher tax bracket, trigger costly Medicare surcharges, and make more of your Social Security benefits taxable. This report demonstrates how this one-year timing mistake can cost thousands and outlines the essential strategies to avoid it.

Deconstructing the RMD: Rules of the Road for the Modern Retiree

Understanding the mechanics and purpose of Required Minimum Distributions is the first step in avoiding their pitfalls. These rules, recently modified by significant legislation, dictate when and how retirees must begin drawing down their tax-deferred savings.

2.1 The Purpose and Evolution of RMDs: The IRS Always Gets Its Share

The fundamental purpose of RMDs is to prevent tax-deferred retirement accounts—such as traditional Individual Retirement Arrangements (IRAs) and 401(k) plans—from being used as permanent tax shelters or as vehicles for transmitting wealth to beneficiaries.

The U.S. government, having granted decades of tax-deferred growth on contributions and earnings, eventually requires the collection of its tax revenue. The RMD framework, which dates back to the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) of 1974, ensures that these funds are distributed and taxed during a retiree’s lifetime.

The Critical Calculation: Your Annual Withdrawal Mandate

Calculating an individual’s annual RMD is a straightforward process based on two key figures: the account balance and a life expectancy factor provided by the IRS.

Determine the Account Balance: The calculation begins with the fair market value of the retirement account as of December 31 of the year preceding the distribution year.

Find the Distribution Period: The IRS publishes the Uniform Lifetime Table (Table III) in Publication 590-B, which provides a “distribution period” based on the account owner’s age for the distribution year. For example, at age 73, the distribution period is 26.5 years; at age 74, it is 25.5 years.

Calculate the RMD: The RMD is calculated by dividing the prior year-end account balance by the distribution period for the current year. The formula is:

RMD=Distribution Period from Uniform Lifetime TableAccount Balance as of Prior Dec. 31

An important exception exists for individuals whose sole primary beneficiary is a spouse who is more than 10 years younger. In this specific circumstance, the retiree can use the IRS’s Joint Life and Last Survivor Expectancy Table (Table II) instead of the Uniform Lifetime Table.

This table provides a longer distribution period based on both spouses’ ages, resulting in a smaller, more tax-friendly RMD.

The First RMD Deadline: Setting the Trap

The rule that creates the RMD trap is explicit and found directly in IRS regulations. An individual who reaches age 73 in a given year must take their first RMD by April 1 of the following calendar year. This is known as the Required Beginning Date (RBD).

However, the RMD for that second year—the year the individual turns 74—is still due by its standard deadline of December 31.

This creates a scenario where two distributions can easily fall into the same tax year. For example, an individual who turns 73 in 2024 has a first RMD (for tax year 2024) that is due by April 1, 2025. Their second RMD (for tax year 2025) is due by December 31, 2025.

If they utilize the delay and take the first RMD in March 2025 and the second RMD in December 2025, both distributions are reported as taxable income on their 2025 tax return, effectively doubling their RMD income for that year.

The Anatomy of the Trap: A Multi-Front Financial Assault

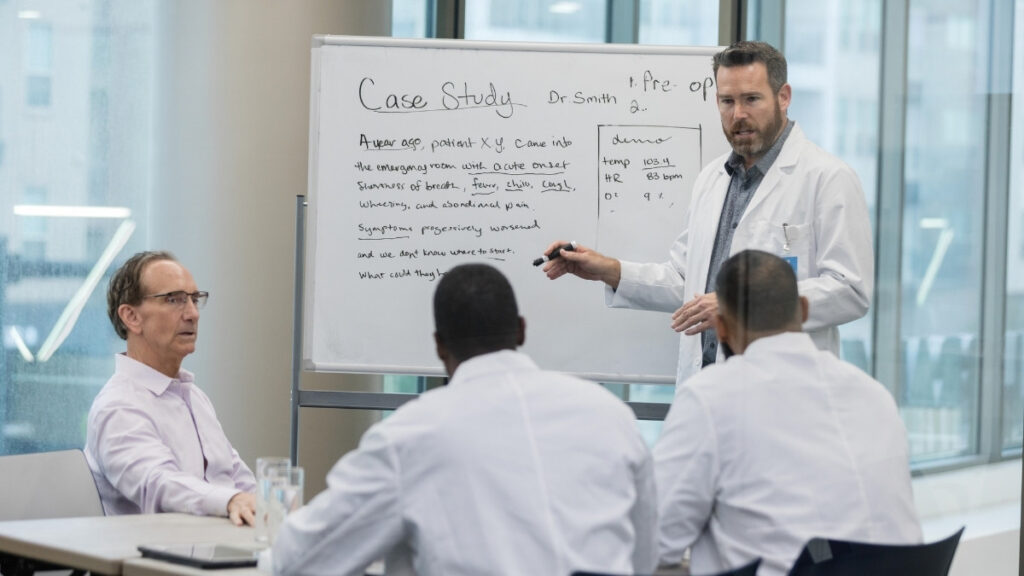

To precisely quantify the financial damage caused by the RMD timing mistake, this section presents a detailed case study. The analysis uses projected 2025 federal tax brackets, standard deductions, and Medicare IRMAA thresholds to model the real-world consequences of bunching two RMDs into a single tax year.

Case Study Introduction: Meet John and Mary

The hypothetical case involves John and Mary, a married couple filing their taxes jointly. John turned 73 in 2024, and Mary is 71. Their financial profile is as follows:

- Assets: John holds a traditional IRA with a balance of $1,500,000 as of December 31, 2023.

- Income: Their baseline annual income consists of $60,000 in combined Social Security benefits and $50,000 from other sources such as pensions and investment interest, for a total non-RMD income of $110,000.

- The Decision: John is contemplating whether to take his first RMD by the end of 2024 or delay it until the April 1, 2025 deadline. This analysis will compare the financial outcomes for their 2025 tax year under both scenarios.

3.2 Calculating the RMDs

John’s first two RMDs are calculated based on his age and prior year-end IRA balances.

- First RMD (for 2024): This is based on his age (73) and the IRA balance on December 31, 2023. Using the distribution period of 26.5 from the Uniform Lifetime Table , the calculation is: RMD1=26.5$1,500,000=$56,604

- Second RMD (for 2025): This is based on his age (74) and the IRA balance on December 31, 2024. Assuming the portfolio grows modestly after accounting for the first withdrawal, the year-end balance is projected to be $1,550,000. Using the distribution period of 25.5 for age 74 , the calculation is: RMD2=25.5$1,550,000≈$60,784

The Final Tally: Quantifying the Mistake

The danger of the RMD trap lies in its creation of a “phantom tax bracket.” The marginal tax rate on the second, delayed RMD is far higher than the statutory 22% rate. This is because each additional dollar of income from that RMD triggers three simultaneous tax effects: the ordinary income tax itself, the cliff-like imposition of the IRMAA surcharge, and, for those on the cusp, an increase in the amount of Social Security benefits subject to taxation.

For some taxpayers, this can result in a marginal tax rate exceeding 40% on those dollars. The income spike from the delayed RMD pushes their MAGI just over the IRMAA threshold, activating a fixed penalty that represents a significant percentage of the income that caused the breach. This compounding, non-obvious tax effect is what makes the trap so financially damaging.

The table below provides a clear, quantitative summary of the cost of John and Mary falling into the RMD trap in their 2025 tax year.

| Metric | Scenario A: Fell into Trap (Two RMDs in 2025) | Scenario B: Avoided Trap (One RMD in 2025) | Annual Cost of Mistake |

| RMD Income | $117,388 | $60,784 | N/A |

| Modified AGI (MAGI) | $218,388 | $161,784 | N/A |

| Taxable Income | $185,188 | $128,584 | N/A |

| Federal Income Tax Owed | ~$28,568 | ~$15,157 | ~$13,411 |

| Medicare IRMAA Surcharge (for 2027) | $2,105 | $0 | $2,105 |

| Total Quantifiable Cost of the One-Year Mistake | ~$15,516 |

The Proactive Playbook: Disarming the RMD Tax Bomb

Avoiding the first-year RMD trap is a crucial defensive measure, but a truly comprehensive retirement income strategy requires a proactive, multi-year approach to managing lifetime RMD tax liability. The goal is to strategically reduce the size of tax-deferred accounts before RMDs begin, thereby shrinking all future mandatory withdrawals and their associated tax burdens.

The Immediate Fix – A Simple Act of Prevention

The primary and most direct recommendation to avoid the financial damage detailed in the preceding analysis is unequivocal: Take the first Required Minimum Distribution by December 31 of the year you turn 73. This simple action ensures the income from the first and second RMDs is recognized in two separate tax years, completely sidestepping the income-bunching trap.

Long-Term RMD Mitigation – Beyond the First Year

Beyond the immediate fix, retirees can employ several powerful strategies in the years leading up to age 73 to fundamentally alter their RMD landscape. These tactics focus on proactively managing the size of tax-deferred accounts to minimize future tax obligations.

Mastering the “Gap Years” with Strategic Roth Conversions

The most potent long-term strategy for RMD mitigation is the strategic use of Roth conversions, particularly during the “gap years.” This period, typically between the date of retirement and the commencement of RMDs and Social Security benefits, is often characterized by uniquely low taxable income, creating a prime opportunity for tax planning.

A Roth conversion is the process of moving funds from a traditional (pre-tax) IRA to a Roth (post-tax) IRA. This action requires the account owner to pay ordinary income tax on the entire converted amount in the year of the conversion. The significant long-term benefits justify this upfront tax payment: all future growth and qualified withdrawals from the Roth IRA are completely tax-free, and, crucially, Roth IRAs are not subject to RMDs for the original owner.

The most effective technique is known as “bracket filling.” This involves systematically converting just enough from a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA each year to “fill up” the lower tax brackets (e.g., the 10%, 12%, and 22% brackets) without pushing income into higher marginal rates.

A case study of a couple named “Jack and Diane” with $1.9 million in tax-deferred accounts illustrates the power of this approach. By executing conversions annually to the top of the 24% tax bracket during their gap years, they were projected to save over $600,000 in lifetime taxes compared to a strategy of simply deferring taxes and facing massive RMDs later in life.

The Power of Philanthropy: Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs)

For charitably inclined individuals, the Qualified Charitable Distribution (QCD) is an exceptionally powerful tool. IRS rules permit individuals aged 70½ and older to donate up to $108,000 (the 2025 inflation-adjusted limit) directly from their IRA to a qualified public charity.

The primary tax benefit of a QCD is that the distributed amount can satisfy all or part of that year’s RMD but is entirely excluded from the individual’s adjusted gross income (AGI). This is a critical distinction. Because a QCD directly lowers AGI, it provides a powerful secondary benefit: it helps the retiree stay below the income thresholds that trigger Medicare IRMAA surcharges and the taxation of Social Security benefits.

This outcome is superior to taking the RMD, recognizing it as income, and then donating the cash, which would only provide a tax benefit to those who itemize their deductions. Given the higher standard deductions in recent years, many retirees no longer itemize, making the AGI reduction from a QCD the most tax-efficient method of charitable giving from an IRA.

4.5 Advanced Tactics for Comprehensive Planning

Two additional strategies can supplement a comprehensive RMD plan:

Qualified Longevity Annuity Contracts (QLACs): A QLAC allows a retiree to allocate a portion of their retirement funds—up to a lifetime limit of $210,000 in 2025—to purchase a special type of deferred annuity.

The amount invested in the QLAC is excluded from the IRA balance used for RMD calculations until annuity payments begin, which can be deferred as late as age 85. This effectively shrinks the RMD base and defers a portion of the tax liability.

The “Still Working” Exception: An individual still employed past age 73 who does not own more than 5% of the company can delay taking RMDs from that specific company’s 401(k) plan until the year they retire. It is critical to note that this deferral applies only to the current employer’s plan and never to IRAs or 401(k) plans from previous employers, from which RMDs must still be taken.

The following table provides a high-level comparison of these long-term mitigation strategies to aid in decision-making.

| Strategy | How It Works | Primary Tax Benefit | Ideal User Profile | Key Limitation |

| Roth Conversions | Pay tax now to move funds from Traditional to Roth IRA. | Eliminates future RMDs from converted amount; creates tax-free income source. | Retirees in “gap years” with lower income; those who expect higher tax rates in the future. | Requires cash to pay taxes on conversion; five-year rule on withdrawals. |

| QCDs | Donate directly from IRA to charity. | Satisfies RMD but excludes the amount from AGI, lowering taxes, IRMAA risk. | Charitably-inclined individuals age 70½+; especially non-itemizers. | Must be 70½+; annual dollar limit ($108,000 in 2025). |

| QLACs | Use IRA funds to buy a deferred annuity. | Excludes the purchase amount from the RMD calculation base until payments begin. | Individuals concerned about outliving their assets who want to defer a portion of RMDs. | Lifetime contribution limit ($210,000 in 2025); funds are illiquid. |

Common Misconceptions and Expert FAQs

Navigating the RMD landscape is fraught with potential for error, often stemming from logical but incorrect assumptions about how the rules operate across different account types and between spouses. Clarifying these points is essential for compliance and effective planning.

Aggregation Rules: Not All Accounts Are Created Equal

A frequent point of confusion is the rule for aggregating RMDs from multiple accounts. The rules differ significantly between IRAs and workplace retirement plans.

The IRA Rule: An individual who owns multiple traditional IRAs must calculate the RMD for each account separately based on its prior year-end value. However, after calculating the total RMD obligation across all IRAs, they can withdraw that total amount from any single IRA or any combination of their IRAs.

The 401(k)/403(b) Rule: This aggregation flexibility does not apply to workplace plans like 401(k)s or 403(b)s. If an individual has accounts from multiple former employers, they must calculate and take the specific RMD from each separate plan.

An RMD from one 401(k) cannot be satisfied by taking a larger withdrawal from another 401(k), nor can an IRA withdrawal satisfy an RMD for a 401(k), or vice-versa.

Spousal RMDs: His and Hers Are Separate

Married couples often assume they can manage their RMDs on a household basis, but this is incorrect. Each spouse is treated as an individual for RMD purposes. The RMD for each spouse must be calculated based on their own accounts and withdrawn from their own accounts.

One spouse cannot take an extra-large distribution from their IRA to cover the RMD obligation of the other spouse. Even if the funds are deposited into a joint account and reported on a joint tax return, failure by one spouse to take their required distribution will result in a penalty assessed to that individual.

The Rollover and Conversion Prohibition

A critical rule that underpins the entire RMD system is that the RMD amount for any given year is ineligible to be rolled over into another retirement account or converted to a Roth IRA. The RMD must be satisfied and distributed first.

Only after the mandatory distribution has been taken can any additional amounts be rolled over or converted. This rule prevents a perpetual cycle of tax deferral and ensures that funds are ultimately distributed and taxed as intended by the law.

5.4 Penalties and Waivers: The Cost of Non-Compliance

Failure to take the full RMD amount by the deadline results in a significant excise tax. The SECURE 2.0 Act reduced this penalty from a draconian 50% to a still-substantial 25% of the amount that was not withdrawn.

The law provides further relief, reducing the penalty to just 10% if the individual corrects the shortfall in a timely manner, typically within a two-year correction window.

Despite the severity of the penalty, the IRS has the authority to waive it. According to retirement tax expert Ed Slott, the IRS is often lenient with taxpayers who make good-faith errors. If a retiree misses an RMD, they should immediately withdraw the required amount, file IRS Form 5329, and attach a letter of explanation detailing the reason for the mistake.

For reasonable causes, such as a calculation error or a misunderstanding of the rules, the IRS has frequently waived the penalty.

Conclusion: From Required Distribution to Strategic Opportunity

The analysis presented in this report demonstrates that the age-73 RMD timing trap is a significant and quantifiable financial hazard.

The seemingly innocuous decision to delay a first RMD by a few months can cost a retiree over $15,000 in a single tax year through a combination of higher federal taxes and avoidable Medicare surcharges. This cost is entirely preventable through a simple act of timely planning.

By employing powerful strategies such as systematic Roth conversions to fill lower tax brackets, charitably-minded individuals can leverage Qualified Charitable Distributions to reduce taxable income, and all retirees can ensure proper timing. These tools allow retirees to transform a required liability into a strategic advantage.

By taking control of their tax destiny well before RMDs begin, they can significantly reduce their lifetime tax burden, minimize healthcare costs in retirement, and preserve more of the wealth they have worked diligently to accumulate.

The final call to action is for all pre-retirees and new retirees to conduct a forward-looking analysis of their own retirement accounts, income sources, and future tax liabilities. Consulting with qualified financial and tax professionals well in advance of the 73rd birthday is not a luxury but a necessity.

Such proactive engagement is the key to developing a personalized RMD strategy that disarms the tax bomb and ensures a financially secure and tax-efficient retirement.